Book review: Deindustrializing Montreal

reviewed by Richard Harris

- Created

- 9 Sep 2022, 10:46 a.m.

- Author

- Richard Harris

- DOI

- 10.1177/00420980221116647

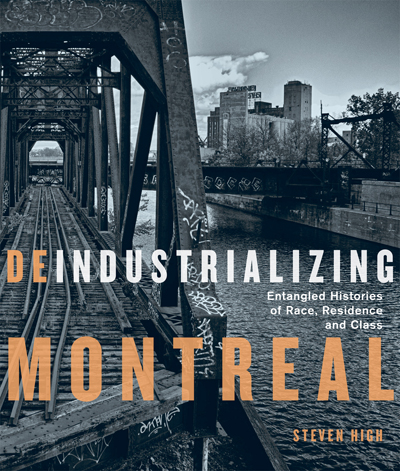

Steven High, Deindustrializing Montreal: Entangled Histories of Race, Residence, and Class, Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022; xvii+419 pp.: ISBN: 978-0-2280-1075-3, CAN$49.95 (hbk), £41.28 (hbk)

Social scientists have written many studies of working-class neighbourhoods and, more recently, of gentrification. What few have attempted is to combine the two by offering a narrative of long-run change. That is what the Canadian historian, Steven High, has done – and very well indeed – in Deindustrializing Montreal.

High offers us a comparative case study of two 19th-century working-class neighbourhoods adjacent to Montreal’s Lachine Canal, tracking how they have evolved since the 1950s. One, Point St-Charles, was industrial and white, mostly anglophone, while the other, now known as Little Burgundy (‘the Burgz’ to local youth), was multiracial, including a black minority many of whose male workers were employed on the railroad. High’s core goal is to explore the subtle interplay of class and race in these local, and specifically Canadian, settings. Both areas were stigmatised, although differently, Little Burgundy as a racialised ghetto and Point St-Charles as a deindustrialised slum. Both are situated in a city which, unlike stereotypical ‘legacy cities’ – a euphemism if ever there was one – has fared quite well. High tells their stories in counterpoint, drawing extensively on oral histories, supplemented by public archives, the records of community organisations, and various photographic collections.

He organises his account as a thematic narrative. In the first section he shows us the work and home lives of the residents of each neighbourhood, exploring the varied interplay of race and class through the 1960s. In the second, he traces how the steady loss of manufacturing jobs, a large urban renewal project in Little Burgundy, and then state-assisted gentrification transformed the two areas, albeit in different ways. In Little Burgundy, renewal plans made no reference to racialised minorities. However, when planners gave the area its current name, they presented it as the historic site of Montreal’s black community, which supported a golden age of jazz that included Oscar Peterson. Meanwhile, Point St-Charles was reinvented more straightforwardly, as the greening of the once-polluted canal helped attract condominium development. Its industrial past was officially noted, but sanitised, as a historic site. In the final section, High examines how residents had used place-based identities, initially to resist plant closings and gentrification, and then to ‘pick up the socio-economic pieces’ (p. 22).

High has done a marvellous job. Not surprisingly, given that he is president of the Canadian Historical Association, this is a scholarly work, serious in intent while being thoroughly researched and referenced. But, perhaps also because the author is a historian and is able to draw on many personal accounts, it is engagingly written. Better still, he draws abundantly on local photographic collections, and it is probably the illustrations, one on every other page and many in colour, that will first attract most readers’ attention. They show homes, cafes, schools, a bonfire, murals, portraits of residents, children, the canal, streets, cartoons, community centres, a library, factories – working, abandoned and reinvented – and, most telling for this reader, some cramped and poorly-lit interiors with workspaces where you can sense the pressure of noise and feeling of dust. Using these, High deftly, and with critical empathy, evokes the experience of local workers and residents. It has clearly been a labour of love. He notes that he has been a resident of Point St-Charles since 2011, contributing to the process of gentrification about which he expresses profound ambivalence. In part, then, Deindustrializing Montreal is a tribute to the area he now calls home.

But it is also much more. For a start, it is a vivid demonstration of something that should be familiar to many readers of this journal: the complicated ways in which the urban setting can heighten social relations. In these districts, proximity fostered intimate cooperation within extended families, between neighbours and co-workers, and more awkwardly across neighbourhoods. Likewise, it heightened conflict, between workers and employers and between residents and incomers, not to mention the municipality when it butted in. Deindustrializing Montreal also shows how, by grounding them in specific settings, local case studies can illuminate large themes, including the complexities of class, race and gender. As such, its early chapters rival the classic studies of working-class neighbourhood ‘urban villages’, including Young and Wilmott’s (1957) portrait of Bethnal Green, and Gans’s (1962) interpretation of Boston’s West End.

Where it is most original, however, is in the deeper resonance that it gives to the effects of gentrification. As High notes at various points, what has been happening since the 1980s in Point St-Charles and Little Burgundy has parallels elsewhere, in cities and neighbourhoods whose experience has been documented by others. But, unusually, what Deindustrializing Montreal does is vividly to show the traditions, lives and experiences of those who gentrification has replaced. It makes us feel what most other studies have only enabled us to know. It is the author’s skill, coupled with an historical perspective, that makes this possible.

But I do have quibbles and reservations. I would dispute High’s suggestion in passing that ‘blight’ is racialised (p. 13); it was routinely applied, for example in Toronto, to any deteriorating neighbourhood thought to be on the downslope to slumdom. Similarly, the claim that studies of gentrification no longer highlight the displacement of existing residents (p. 19) is debatable. Canadian urbanists like myself might wish that High had made fuller comparisons with anglo-Canadian cities. His observations about the effects of urban renewal parallel, and resonate with, previous studies of Toronto and Vancouver; the character of neighbourhood resistance and organisation, which generally gathered momentum relatively late in Montreal, could have been fitted into the established narrative of the Canada-wide neighbourhood movement of the 1960s and 1970s; and an obvious Canadian counterpoint for his description of industrial work and life would have been Heron’s (2015) study of Hamilton, Ontario, the nation’s most industrial city.

More substantially, important geographical strands to the argument could have been probed by tapping the census. High argues that the two neighbourhoods were tight-knit communities, with people living and working nearby, but which then dissolved. Drawing on oral accounts, he also makes specific claims about the changing social composition of the neighbourhoods, and of subareas. In each case, he is probably correct. But details and timing are important. Oral accounts are suggestive, but we know that, in retrospect, residents and researchers often portray tighter communities than in fact existed. Census data on occupation and commuting, together with maps of those data, would have provided an invaluable counterpoint. Given the extended publication schedules of academic publishers, Leloup and Rose’s (2020) account of changing neighbourhood inequality in Montreal may not have been available in time. Published in a definitive Canadian collection of essays, they provide an invaluable, missing context to High’s study.

Stepping back, Deindustrializing Montreal prompts a larger question. Across the English-speaking world, and indeed beyond, social scientists and historians have written many accounts of ‘slums’, ghettoes and working-class neighbourhoods, along with the ways some have revived while others have stagnated or fallen apart. As professionals, we have created many fewer portraits of middle-class, and even fewer of elite, areas. Is this because such areas, and their residents, are relatively accessible to research? Or has this been this our collective attempt – deliberate or subconscious – to show social injustice, to explore the unknown, or perhaps to salve our consciences? I suspect the answer is yes.

References

Gans H (1962) The Urban Villagers: Group and Class in the Life of Italian-Americans. New York, NY: Free Press of Glencoe.

Heron C (2015) Lunch Bucket Lives: Remaking the Workers’ City. Toronto, ON: Between the Lines.

Leloup X and Rose D (2020) Montreal: The changing drivers of inequality between neighbourhoods. In: Grant JL, Walks A and Ramos H (eds) Changing Neighbourhoods: Social and Spatial Polarization in Canadian Cities. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press, pp.101–125.

Young M and Wilmott P (1957) Family and Kinship in East London. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Related articles

If you enjoyed this review, the following articles published in Urban Studies might also be of interest:

|

Gentrification and Social Mixing: Towards an Inclusive Urban Renaissance? By Loretta Lees Lees argues that, "new policies of social mixing require critical attention with regard to their ability to produce an inclusive urban renaissance and the potentially detrimental gentrifying effects they may inflict on the communities they intend to help." |

Belonging in working-class neighbourhoods: dis-identification, territorialisation and biographies of people and place by Jenny Preece Why do people remain in weak labour market areas rather than moving to places of greater employment opportunity? |

Read more book reviews on the Urban Studies blog.

Comments

You need to be logged in to make a comment. Please Login or Register

There are no comments on this resource.