Book review: Making Mexican Chicago: From Postwar Settlement to the Age of Gentrification

reviewed by Evelyn Ravuri

- Created

- 25 Jan 2023, 10:39 a.m.

- Author

- Evelyn Ravuri

- DOI

- 10.1177/00420980231151785

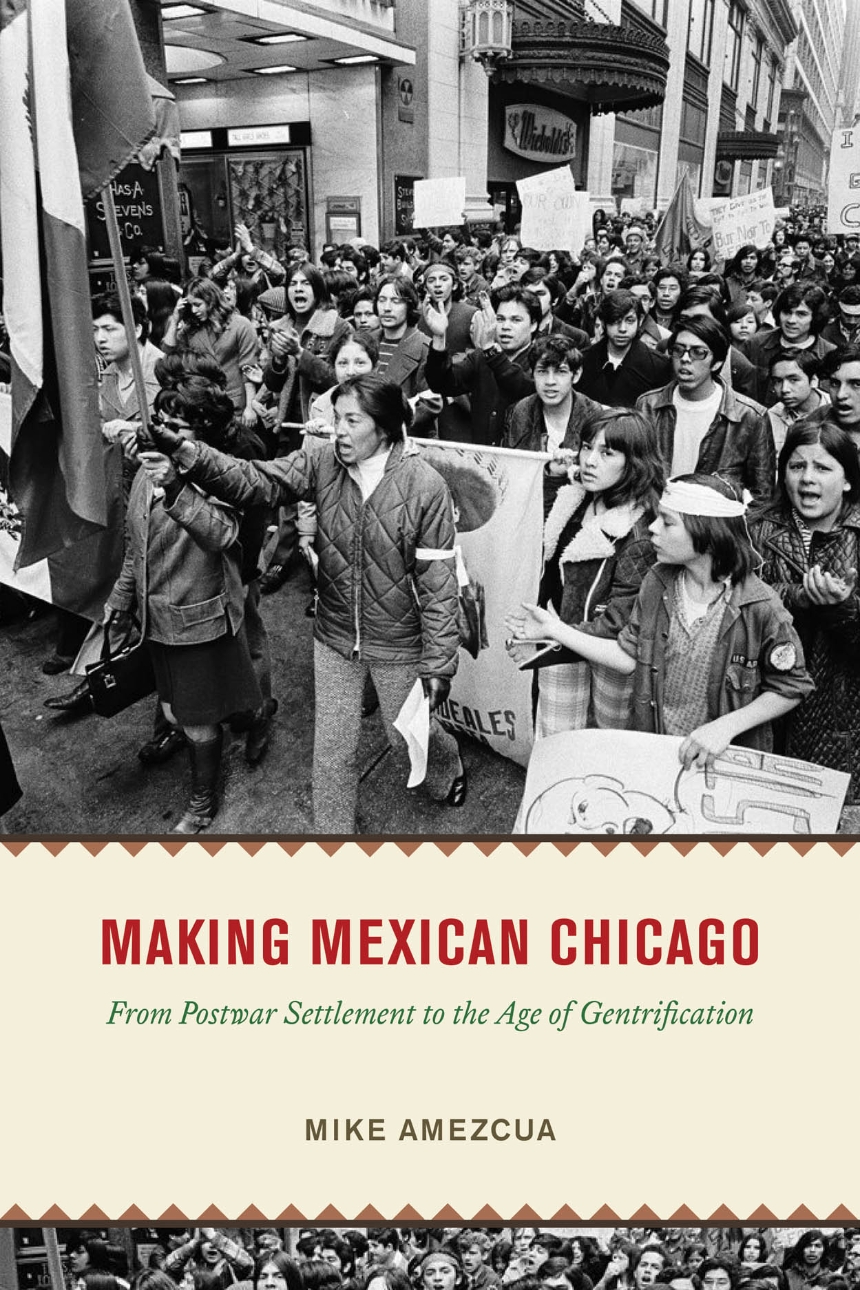

Mike Amezcua, Making Mexican Chicago: From Postwar Settlement to the Age of Gentrification, Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2022; 331 pp.: ISBN: 9780226815824, £36.00/US $45.00 (cloth); ISBN: 9780226826400, £20.99/US $25.00 (paperback); ISBN: 9780226815831.

In Making Mexican Chicago: From Postwar Settlement to the Age of Gentrification, Amezcua chronicles the 20th-century struggle of Mexicans/Mexican Americans to win a place in Chicago’s economic and political structure. Unlike European immigrants who culturally, linguistically and visually blended into white society over time and were able to pursue the ‘American Dream’, Mexican immigrant status lingered long after settlement. Mexican/Mexican American otherness (in this case skin colour) was a marker that followed them throughout acclimatisation and precluded access to many of Chicago’s neighbourhoods. Like pawns in a chess game, Mexicans/Mexican Americans were moved about and/or removed from Chicago’s neighbourhoods and sacrificed for the benefit of the ‘white queen’ (capitalists). While a few ‘black knights’ (Mexican American organisations) were able to wrest economic and political power for Chicago’s Mexican American population, gentrification – the in-migration of middle-class whites (facilitated by capitalism) – effectively led to ‘checkmate’ for several of Chicago’s ethnic Mexican neighbourhoods by the early 2000s. This analogy to a chess game overdramatises Amezcua’s argument, but this is the feeling that this reviewer takes away from the book.

Making Mexican Chicago comprises six chapters that focus on the following Chicago neighbourhoods: the Near West Side, Back of the Yards, South Lawndale and Pilsen. Chapter 2, ‘Deportation and Demolition’, discusses Chicago’s slum clearance projects of the 1950s/1960s and the plans to build the University of Illinois Chicago Campus in the Near West Side, the heart of the Mexican community at that time. Revitalising the Near West Side was crucial to Chicago’s economic future in that the twin processes of suburbanisation and deindustrialisation had significantly drained city finances. The 1952 McCarran–Walter Act (referred to pejoratively as Operation Wetback) was used to deport undocumented Mexicans who had become a drain on Chicago’s economy. In fact, ‘Operation wetback … was a momentary boon to the sagging regional economy as the INS repurposed a deindustrialising landscape for the business of detention and deportation’ (p. 39). Unfortunately, the precarious immigrant status of Chicago’s Mexican population made it difficult to organise and fight for civil rights.

Chapter 3 focuses on the Back of the Yards neighbourhood; a stronghold for the white working class and a battleground for the sharing of urban space with a growing Mexican/Mexican American population. Whereas the USA used immigration policy to remove ‘unwanted’ Mexican immigrants from the country (Chapter 2), the City of Chicago used zoning policy to contain Mexican Americans within the least desirable areas within Back of the Yards. In effect, Ashland Avenue became a ‘wall and restricted Mexican dispersal’ (p. 98); analogous to the contemporary ‘wall’ at the US–Mexico border. However, by corralling Mexicans into a spatially concentrated area, Chicago’s Mexicans/Mexican Americans were able to begin to mobilise for political power. Unfortunately, these early political organisations (1950s/1960s) focused on ‘influence building among the white ethnic power structure through sociable displays of respectability’ (p. 86), not on large-scale political protest or revolt.

In Chapter 4, ‘Making a Brown Bungalow Belt’, Amezcua discusses how spatial restrictions on settlement were loosened in several Chicago neighbourhoods when it became apparent that Mexicans/Mexican Americans were needed to infuse demographic and economic life into declining inner-city neighbourhoods after the mass exodus of whites to the suburbs beginning in the 1960s. ‘White evacuation opened up a landscape of opportunity for Mexican Americans once confined to enclaves in Pilsen and Back of the Yards’ (p. 145), while ‘Little Village’s (South Lawndale) entire housing market became dependent on cash-carrying Mexican homebuyers’ (p. 144). However, while Mexican Americans had improved their economic position in Chicago, they were still yet to flex their political muscles.

In Chapter 5, ‘Renaissance and Revolt’, Amezcua examines the Mexican/Mexican American struggle for political power in Chicago commencing in the 1960s. Unfortunately, this pursuit of political power by Chicago’s Mexican ancestry population was complicated by the division of party allegiance between the Republican and Democratic parties – a division that worked to the advantage of the white majority. Mexican Americans associated with the Republican party (mostly the middle class and/or business owners) were more interested in economic development in their neighbourhoods and in aligning themselves with the white power structure. In contrast, Democrats (mostly Chicano activists) worked to empower the entire Mexican American community. Activists saw the economic renaissance of Mexican American neighbourhoods as a second go-round for more ‘cultural erasure and people removal’ (p. 173), and transformed Pilsen’s built environment through a process of mural painting (highlighting political figures in Mexican history) and planting of urban gardens (to draw attention to the lack of greenspace in ethnic Mexican neighbourhoods). The modification of the built environment was an indicator to all that Chicago’s Mexican American population had a rightful and an enduring place in the City’s urban landscape – politically, economically and culturally.

Chapter 6, ‘Flipping Colonias’, focuses largely on the gentrification of Pilsen in the 1990s. The essence of this chapter is that Mexican Americans did too good a job of revitalising Pilsen (and other neighbourhoods) and priced themselves out of the neighbourhood. These urban spaces could now command a higher price per unit of land and attract real estate investors, resulting in displacement of Mexican Americans to other neighbourhoods of the city as well as to Chicago’s suburbs. Unfortunately, Amezcua spends little time on a discussion of the broader issue of suburbanisation of the Hispanic population in Chicago (a process occurring throughout the USA). This oversight is unfortunate in that as of 2020, 61.4% of Hispanics in the USA resided in suburbs, up from 49.5% in 1990 (Frey, 2022), making this a topic worthy of discussion. While a percentage of Mexicans/Mexican Americans were able to improve their economic circumstances and move to Chicago’s suburbs to pursue the ‘American Dream’, many others have been relegated to less than desirable living conditions in Chicago’s inner-ring suburbs. Many 21st-century inner-ring suburbs in cities throughout the USA are burdened with ageing infrastructure and financial disinvestment. A more thorough discussion of the ‘suburbanisation of poverty’ (see Allard, 2017) and how it has affected Chicago’s Mexican American population would have been a good addition to this chapter.

The concluding chapter ends on a pessimistic note: ‘the making of Mexican Chicago has been the story of the pursuit of sanctuary even when it is far from reach’ (p. 248). As of the early 21st century, Pilsen’s built environment retained little evidence of former Mexican American presence, having been supplanted by up-scale boutiques, breweries, coffee shops, restaurants and condominiums to cater to the ‘creative class’. The ‘creative class’, a term coined by Florida (2002), refers to a well-educated and talented labour force (e.g. professionals, artists, entrepreneurs) and is thought to be the key to economically revitalising US cities. This reader was left wondering why a more thorough discussion of Florida’s (2002) work was not included.

In summation, Mexican immigrants/Mexican Americans settled in some of Chicago’s least desirable neighbourhoods, used ‘sweat equity’ to transform these neighbourhoods into economically and culturally viable entities and then were swept aside by the rising tide of gentrification. Unlike European immigrants, who could meld into US society over time, Mexican immigrants (and US-born people of Mexican ancestry) maintained the stigma of ‘foreignness’, and continue to do so. Most importantly, precarious immigration status hampers political power. Throughout the book, Amezcua references different political clubs/organisations that fought for Mexican/Mexican American rights within Chicago. Often, these efforts were underorganised or at cross purposes. The concluding chapter would have been stronger if the author had summarised these political divisions and suggested a path forward for the political inclusion of the Mexican American population in Chicago, as well as in other US cities where the Mexican population has been marginalised economically, spatially and culturally. The book would make an excellent read for any number of college courses examining the intersection of race/ethnicity with economics, politics and culture in US cities.

References

Allard SW (2017) Places in Need: The Changing Geography of Poverty. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. Google Scholar

Florida R (2002) The Rise of the Creative Class. New York, NY: Basic Books. Google Scholar

Frey WH (2022) Today’s Suburbs Are Symbolic of America’s Rising Diversity: A 2020 Census Portrait. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institute. Google Scholar

Related articles

If you enjoyed this review, the following articles published in Urban Studies might also be of interest:

|

'Mexicans love red' and other gentrification myths: Displacements and contestations in the gentrification of Pilsen, Chicago, USA by Winifred Curran On the constantly shifting terrain of gentrification politics in Chicago. |

Minority groups in the metropolitan Chicago housing market: 1970-2015 by John F. McDonald Trends in the housing market of metropolitan Chicago. |

Read more book reviews on the Urban Studies blog.

Comments

You need to be logged in to make a comment. Please Login or Register

There are no comments on this resource.