Book review: Non-Performing Loans, Non-Performing People. Life and Struggle with Mortgage Debt in Spain

reviewed by Isabel Gutiérrez Sánchez

- Created

- 20 Jun 2023, 10:48 a.m.

- Author

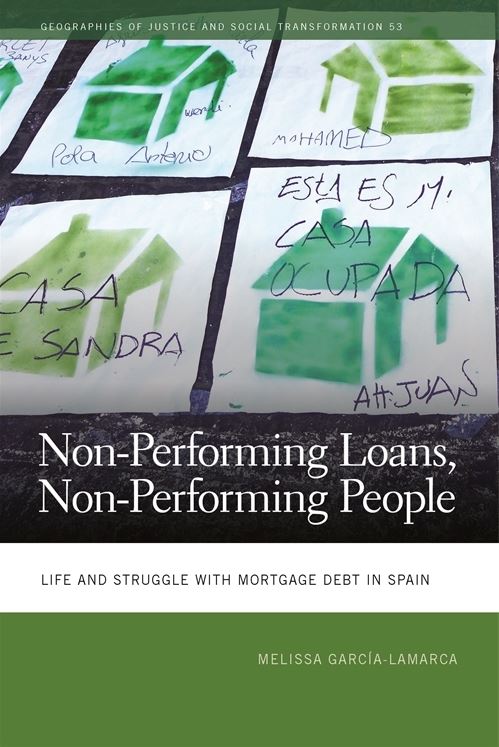

Melissa García-Lamarca, Non-Performing Loans, Non-Performing People. Life and Struggle with Mortgage Debt in Spain, Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2022; 240 pp.: ISBN: 978-0-8203-6300-4, £27.99/$29.95 (pbk), ISBN: 9-780-8203-6299-1, $114.95 (hbk)

How does financial speculation with housing serve contemporary processes of urban capital accumulation and how does it affect everyday lives? How does mortgage debt shape subjectivities? How can these processes be disrupted? What are the emancipatory possibilities of collective resistance to indebtedness? Non-Performing Loans, Non-Performing People. Life and Struggle with Mortgage by Melissa García-Lamarca addresses these questions connecting wider processes of housing and life financialisation at the political–economic macro-level with lived experiences of people hit by mortgage debt as well as (ex-)bankers and former government employees in the Barcelona metropolitan region. Drawing on a long-term engagement as a researcher and activist with the housing rights initiative Platform for Mortgage Affected People (PAH), García-Lamarca carries out an intersectional analysis that sheds light on the differentiated debt ecologies (Harker, 2020) resulting from the financialisation of housing in Spain.

The book focuses on two main periods, namely the housing boom or the ‘urbanisation tsunami’ (Fernández Durán, 2006) that took place in the country from 1997 to 2007 and the post-2008 crisis. To facilitate the understanding of the production and development of the Spanish financialised housing model, García-Lamarca initially provides a historical account that unpacks the main economic, political and ideological dimensions of housing during the second half of the 20th century. The research underpinning the book is articulated in three interconnected theoretical and analytical strands, namely the financialisation of housing – and life more broadly – the biopolitics of mortgage debt and processes of political subjectivation. They serve to structure the book and ground its central claims.

In the first chapter, García-Lamarca builds upon both macroeconomic and everyday life theoretical approaches to financialisation to ground her examination of the various ideological, institutional and legal transformations through which housing ownership and financialisation were gradually introduced and enabled in the Spanish context. She explains how the promotion and production of housing and homeowners initially during the Francoist dictatorship and then under democracy and parallel processes of Europeanisation were driven by the will to create and sustain a specific socio-economic order. Namely, one focused on construction and infrastructure as the main sectors to drive economic growth, and on homeownership as a key mechanism for social control – first more specifically as a means for racial regeneration to form ‘first-class’, Catholic, tradition-abiding, patriotic Spaniards during the Franco regime, and then as a way to adjust the population to the processes of market liberalisation. From state-subsidised housing to the restructuring of housing policies, land use and mortgage finance in the 1980s and 1990s, these state-driven reforms laid the groundwork for the real estate boom that profoundly transformed Spain from 1997 to 2007.

In the second chapter, García-Lamarca examines this period of unprecedented housing expansion through the Foucauldian lens of biopolitics, which the philosopher conceptualised to refer to forms of social control of human bodies and populations through varied political techniques and technologies of the self. García-Lamarca shows how housing mortgages were normalised both by the state and the private sector, which constantly promoted them as a safe investment disguising them as household wealth. This way their complexity as financial products was masked, and instead buying a house through a mortgage was portrayed as common sense. Both legal and regulatory mechanisms as well as discourses of non-choice played a key role in this normalisation of mortgage debt. Thus, they can be viewed as controlling and disciplinary technologies in that they produce populations forced to produce to meet their debts, which in turn affects individuals on a subjective and corporeal level. Following Lazzarato (2012), García-Lamarca states that ‘paying mortgage debt is a form of discipline and is […] a relation of both self-inflicted and externally imposed subjection’ (p. 23). It is in this sense that she speaks of ‘mortgaged lives’, a concept that she coined together with Kaika (García-Lamarca and Kaika, 2016) in a previous research paper. Notwithstanding, she highlights through a well-grounded ethnographic analysis, different lived experiences among these mortgaged lives depending on aspects of race, class and gender upon which financing and housing were accessed. The financialisation of housing creates differentially indebted people.

García-Lamarca continues this intersectional analysis in her examination of the post-2008 crisis in the third chapter. The national economic crisis that followed the collapse of the international financial sector had a rapid effect on household mortgages, many of which became non-performing. In 2012, Spain’s financial sector was bailed out and restructured following the conditions imposed by the EU. During these years, the regulatory and disciplinary techniques of the established financialised housing model were reconfigured – and hardened – to ensure the circulation of capital. In this sense, García-Lamarca argues that non-performing loans were de facto equated to non-performing people. Many non-performing mortgaged households were forced to refinance their mortgages, take grace periods or accept credit offers to keep paying their mortgages, getting further indebted in this way. García-Lamarca traces the profound societal consequences of these measures and operations and their impacts on people’s livelihoods, everyday lives and bodies, highlighting aspects of guilt, shame, fear and health issues including depression and suicide attempts.

The last chapter of the book is dedicated to the analysis of processes of formation of political subjectivities that unfold in collective struggles against this system of housing financialisation. Here, García-Lamarca focuses on the transformations that take place at both the material and subjective levels when people challenge and break debt relations collectively. Through her engagement with the Platform for Mortgage Affected People (PAH) in the metropolitan region of Barcelona, she traces changes in people’s positions and self-identifications as they participate in weekly collective advising assemblies and direct actions including blocking evictions, occupying banks and recuperating empty bank-owned housing. Engaging with Rancière (1992, 2008), she nonetheless argues that political subjectivities are formed through collectively learned practices over time rather than as the result of single events or acts of disruption. ‘These learned practices move directly against the dominant individualized and individualizing logic of the indebted person […] Critically, these collectively learned practices are an illustration of how the PAH is a social process that generates its own analysis, concepts, experiences and practices’ (p. 172). Importantly, she highlights that these processes are not linear or even. On the contrary, they are marked by challenges and contradictions. García-Lamarca notes, for instance, the scarcity of awareness and measures to address racialised dynamics within the movement.

Overall, Non-Performing Loans, Non-Performing People. Life and Struggle with Mortgage provides a telling and nuanced story of how housing acts as a key component of contemporary processes of capital extraction and people’s exploitation particularly in urban contexts, how financial speculation through housing differentially affects people’s lives, bodies and subjectivities and how engagement in collective initiatives of resistance can create ruptures in these multi-scalar dynamics. The book renders visible these entanglements highlighting how race, class and gender introduce significant variations in these processes and dynamics. This way, it makes an outstanding and much needed contribution to ongoing scholarly and political debates on the financialisation of life that marks our contemporary world. The book is of special relevance to the field of urban studies in that it deepens the critique of the financialised housing model as entangled with processes of urban capital accumulation, elaborates on its consequences on everyday urban life, and provides insights into alternatives towards more just urban and housing futures. Notwithstanding, the most generative finding of the book is perhaps that that points out the collective learnings as bearers of the most transformative capacity to disrupt both material and subjective logics of indebtedness and its associated extraction and exploitation. With it, García-Lamarca has opened up a line of inquiry and interdisciplinary research deeply relevant to present social justice movements and scholarship.

References

Fernández Durán R (2006) El tsunami urbanizador español y mundial. Boletín CF+S 38/39: 1–43. Google Scholar

García-Lamarca M, Kaika M (2016) ‘Mortgaged Lives’: The biopolitics of debt and homeownership in Spain. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41(3): 313–327. Crossref; PubMed; ISI; Google Scholar

Harker C (2020) Spacing Debt: Obligations, Violence, and Endurance in Ramallah, Palestine. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Google Scholar

Lazzarato M (2012) The Making of the Indebted Man: An Essay on the Neoliberal Condition. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e). Google Scholar

Rancière J (1992) Politics, identification, and subjectivization. October 61: 58–64. Crossref; Google Scholar

Rancière J (2008) The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. Translated by Gabriel Rockhill. London: Continuum. Google Scholar

Related articles

If you enjoyed this review, the following article published in Urban Studies might also be of interest:

|

From housing crisis to housing justice: Towards a radical right to a home by Valesca Lima Lima explores the ways housing movements in Dublin use direct and confrontational approaches as political action. |

Read more book reviews on the Urban Studies blog.

Comments

You need to be logged in to make a comment. Please Login or Register

There are no comments on this resource.