Book review: Streetcars and the Shifting Geographies of Toronto

reviewed by Rebecca Heimel

- Created

- 13 Jan 2023, 10:07 a.m.

- Author

- Rebecca Heimel

- DOI

- 10.1177/00420980221144187

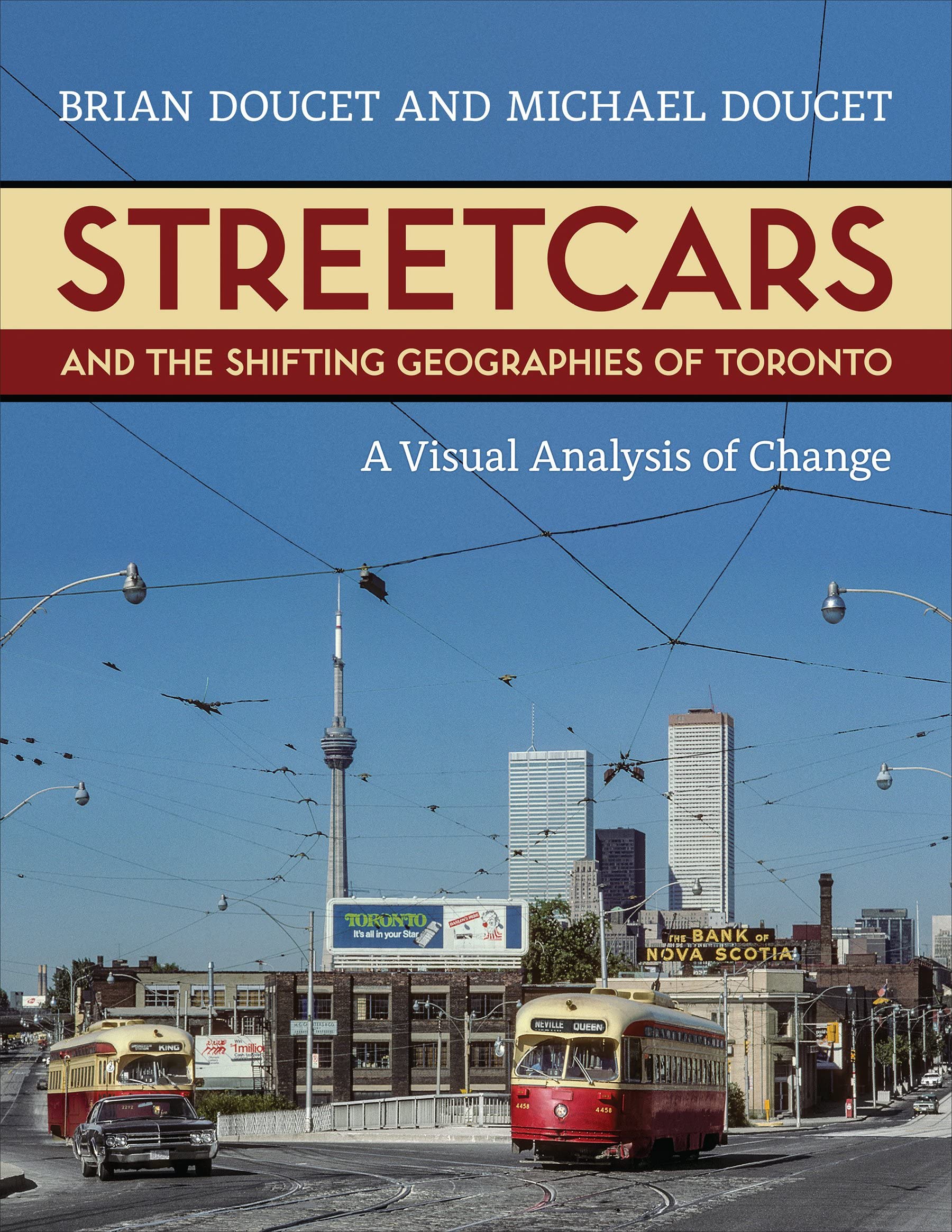

Brian Doucet and Michael Doucet, Streetcars and the Shifting Geographies of Toronto, Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2022; 320 pp.: ISBN: 978-1487500108, $49.95 (pbk)

Photography and related visual practices render visible what is often invisible when looking at statistics alone. We need new ways of looking at cities, and practices traditionally found in the arts and humanities offer us a way forward. Doucet and Doucet, a father and son academic team, are the first to analyse the urban, economic, social and geographic realities of Toronto using urban scholarship together with the method of repeat photography on historic and contemporary images of streetcars. Repeat photography is a practice of rephotographing the same location or subject at different moments in time. The result of their analysis is an integrated and thorough understanding of ‘uneven geographies’ (p. 3) and their visual manifestations throughout the city. Doucet and Doucet have provided a text that bridges a deep divide between academic research and planning and policy debates.

There are only nine cities in North America that have legacy systems of electric, street-running public transit and Toronto’s streetcar system boasts the highest ridership among them. Toronto was progressive in the post-World War II years, adding to its streetcar systems even as other cities were abandoning their systems or reducing them in size. An effort by community activists in the 1970s saved the system from replacement by bus. The Toronto streetcar system is a key example of a ‘network effect’ that allows passengers within a city to transfer from route to route via public transport in order to reach nearly all parts of a city, much like the way motorists navigate road systems. Streetcars are not uncontroversial in Toronto. Doucet and Doucet outline the divide between suburban and urban populations and point to those who would prefer that the city prioritise parking and automobile rights-of-way over public transportation. Nonetheless, streetcars are an iconic image of the city, part of the heritage and self-image of many Torontonians and often used as a symbol of the city itself.

Doucet and Doucet, themselves streetcar enthusiasts, employ photography and visual analysis to look not just at streetcars but also at the area around them in order to determine change over time. Many streetcar enthusiasts in North America travel from city to city taking amateur, though high quality, photographs of streetcar transit systems. This tradition has been in place since the 1930s and originated with railway enthusiasts, continuing through until today; the majority of the original images in the Doucets’ text date from the 1960s and 1970s. For most fans, the streetcars themselves are the primary focus of their photography and the capturing of any surrounding area was an unintended consequence. Rather than the usual ‘tourist gaze’ of a few major parts of cities, streetcar enthusiasts inadvertently but rather thoroughly document cities in the background of each of their shots. The images that survive, many of which are in private collections and relatively unknown beyond the subculture that produced them, are not only of very high quality but also capture parts of major North American cities that otherwise might not have been documented. The authors seize the opportunity this affords to refocus these images for the reader in order to draw out secondary contents. This affords us a look at, an analysis of, the everyday of the last 60 years in Toronto.

James Baldwin insisted on the right to criticise the United States precisely because he loved it so much. The same spirit underlies Doucet and Doucet’s text, and their genuine fondness for their Toronto home carefully frames and shapes their treatment of its history and current issues. Toronto’s rapid change over the last 60 years has produced an income-polarised city in which spatial locations of wealth and poverty and income distribution paint an ominous picture. Though Toronto is part of a wider process of change shaping global cities, it is noteworthy that that its financial sector was on the rise at the same time that industry was in decline, and that its population increased while the population of other cities in the Great Lakes region declined. Now Canada’s global metropolis, Toronto aligns with John Friedmann and Goetz Wolff’s ‘world cities hypothesis’ that argues that a city’s relationship to the ‘new international division of labor’ determines its own economic structure as well as its hierarchy among other cities. Doucet and Doucet carefully outline how neoliberalism has taken form in Toronto, noting the city’s quest for urban status as a priority over urban inclusion. While Toronto has a rich history of major public investment, civic investments in the current era prioritise high-profile developments, major publicised events, and construction of places primarily for tourists and affluent citizens.

The paradox of urban planning is that well-designed, vibrant communities most often exclude those who cannot afford to live there. The core of Toronto, the ‘Streetcar City’, is such a place. Deindustrialisation has occurred unevenly across the city so that virtually no heavy manufacturing is present in the revitalised urban core, precisely where streetcars can be found. Industries such as automotive manufacturing and sorting and warehousing facilities remain in the suburbs of the city, but major factory closures through the 1980s and rising downtown real estate values have pushed that industry further and further out. Policy responses have produced social and cultural benefits, but the authors demonstrate that not everyone has benefited. Structural and spatial inequalities function at the neighbourhood level to displace and exclude, fragmenting services and amenities. The text asks and answers important questions that help readers think differently about revitalisation, considering both the history and current realities of Toronto through visual changes.

Repeat photography is a practice employed across multiple disciplines and to multiple ends. Jon Rieger used the method within sociology to document social change using systematic visual documentation in rural communities. Camilo José Vergara used repeat photography in urban settings, meticulously documenting change over the course of decades in American cities. Repeat photography allows The Doucets to expertly interpret both fine-grained detail and broad patterns within the frame, with a focus on the urban core of Toronto. That which is not immediately visible inside the frame is also a focus of the discussion, which contributes to a complex questioning and affirming of the method of repeat photography even as it is being employed. The authors are clear that original images of streetcars, their point of departure for the ‘repeat’ that they have most often shot themselves, have their limitations. What we do not see in these images becomes as important as what is visible, including that nearly all the images taken of original streetcars are photographed by men. The larger shifts that are captured, or not, are also limited by what we can see. The authors argue that deindustrialisation is not complete. It is just moved outside of the frame.

Doucet and Doucet’s text should be recognised as a contemplative and reflective piece of slow scholarship. They are generous as writers, sharing their personal stories and experiences of the city from their unique generational perspectives, and speaking generally about intergenerational practices as they situate themselves personally within the story of the city of Toronto. They have also considered all possible audiences, allowing the reader clear permission to read out of order, or to look first at images as so many of us want to do. The book is structured to provide six chapters of introduction and context for the photos, followed by three portfolios: ‘Downtown’, ‘(De)Industrialisation’ and ‘Neighbourhoods’ with most pages presenting an image from the 1960s or 1970s together with a contemporary image. The book concludes with two excellent chapters; the first interprets the visual change presented in the portfolios of repeat photography. The final chapter suggests socially just solutions to the issues exposed through the preceding analysis.

The book easily functions as an urban civics text for the 21st century, useful particularly for those citizens of global cities to understand complex processes of globalisation, revitalisation, transit-induced gentrification, and splintered urbanity. There are many academic audiences for the book, especially those in urban studies. As it shares similar methods, those in the ascendant field of urban humanities would also find the text of particular interest.

Separating politics and aesthetics is difficult, if not impossible, according to Doucet and Doucet. They have proved that impossibility by unifying often divided issues of housing, transit, gentrification, racism, economic development and revitalisation, all through visual analysis. To understand Toronto differently we must see it differently, and Streetcars and the Shifting Geographies of Toronto allows us to do just that.

Related articles

If you enjoyed this review, the following articles published in Urban Studies might also be of interest:

|

Seeing the street through Instagram. Digital platforms and the amplification of gentrification by Irene Bronsvoort and Justus L Uitermark Elaborating on the concept of ‘discursive investing’ introduced by Zukin et al., Bronsvoort and Uitermark address these questions in a case study of Javastraat, a shopping street in a gentrifying neighbourhood in Amsterdam East. |

Cities in music videos: Audiovisual variations on London’s neoliberal skyline by Tania Rossetto and Annalisa Andrigo Rossetto and Andrigo highlight how the analysis of music videos can contribute to an appreciation of the multiple and nuanced ways in which skylines are mediated/practiced in the neoliberal age. |

Read more book reviews on the Urban Studies blog.

Comments

You need to be logged in to make a comment. Please Login or Register

There are no comments on this resource.