Book review: Terraformed: Young Black Lives in the Inner City

reviewed by Alexandros Daniilidis

- Created

- 25 Jan 2023, 9:43 a.m.

- Author

- Alexandros Daniilidis

- DOI

- 10.1177/0042098022114972

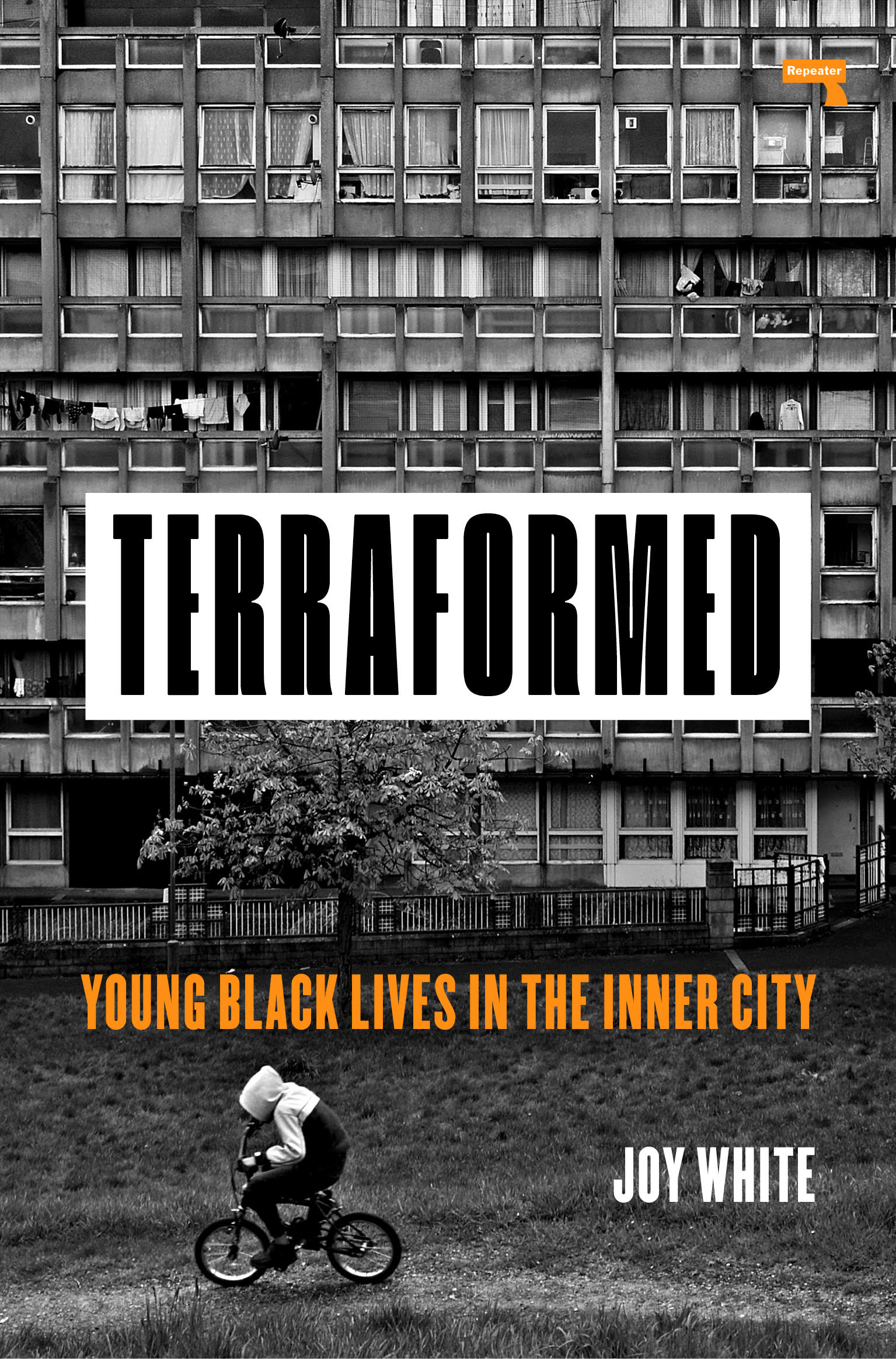

Joy White, Terraformed: Young Black Lives in the Inner City, London: Repeater Books, 2020; 164 pp.: ISBN 978-1912248681, £10.99 (pbk)

Part memoir and part urban ethnography, Joy White’s Terraformed: Young Black Lives in the Inner City aims to record and highlight the underlying forces responsible for creating and sustaining inequalities, poverty and systemic racism in urban settings of the Global North. By employing the inner-city of Newham in East London as a case study, Joy White’s account offers a critical view on the dynamics between neoliberalism, austerity, the changing urban environment and music, while analysing how these issues affect young Black lives. In a highly capitalised system where ‘in order for some to make it to the top, the majority must remain at the bottom’ (p. 2), Terraformed raises timely and revealing questions: what does being young and Black in inner-city communities entail and how do they respond to these hostile conditions?

In the first chapter, White commences by setting the socio-economic context of East London of which Newham constitutes a significant borough. Being in a close proximity to the historical epicenter of the city’s naval trade (the Royal Docks), East London ‘was viewed as a foreign land, situated in the shadow of the wealth of the City and populated by communities of poor people and migrants’ (p. 8). Beginning in the 1950s, the area was initially populated by Caribbean and Asian migrants with the later addition of Black Africans, thus rendering Newham a site of migration and multiculturalism with a working class profile. White then continues with a brief, albeit informative, outline of contemporary issues (outcomes of neoliberalism, austerity and policies) that local migrant communities face. With an emphasis on housing (old, derelict stock) and financial hardship (poverty and unemployment rates), White concludes with contemporary Forest Gate as a ‘Growth Borough’ (p. 19), considering it a ‘place of contrasts’ (p. 23) that, despite being desirable in terms of housing and urban multicultural living, is portrayed as a site of economic and social inequality.

Chapter 2 is titled ‘Neoliberal times’ and, as the title implies, the author engages with an exploration of the emergence of neoliberalism (with the Thatcher years as the starting point) in order to historically locate the development of conservatism that has been affecting migrant populations in Britain. As White states, contemporary Forest Gate ‘is a complex mesh of gentrification, inequality, everyday multiculturalism and violence’ (p. 25) that extends between symbolical value and structural effect. White then further investigates issues regarding residential rehabilitation, replacement, violence, public policies that decimate social contracts and the sonic landscape, with a particular focus on the chronic consequences on Black lives. An important framework employed to investigate these dynamics – and an outstanding contribution of this book – is the one referred to as ‘hyper-local demarcation’. According to White, employing this methodological framework ‘allows us to examine how legislation, communities, the sonic landscape, and town planning come together at the level of the street and make an impact on young Black lives’ (p. 37).

In the subsequent chapter entitled ‘Why music matters’, White introduces Grime as an accessible musical practice for Black youth and underlines its significance as a formative agent of place and (local) identities. Grime is a carrier of Afro-Caribbean cultural heritage and a ‘hyper-localised sound’ that acts as ‘a sonic representation of the spaces their creators occupy’ (p. 41). The use of some iconic examples of Grime music in this chapter is particularly efficient since it provides the reader (who might not be accustomed to the East London Grime scene) with some good musical context. Essentially, in Chapter 3, the author portrays musical expression, interwoven with the area’s social conditions, as the voice of resistance and a cry for recognition and visibility of a whole generation of ‘others’. As White writes, Grime ‘enables them to resist, in multiple ways, the marginal roles that have been mapped out for them’ (p. 49).

Chapter 4 connects contemporary Forest Gate and Newham with the social phenomenon of gentrification by exploring the constructed ‘desirable’ character of the neighbourhood from WOW (well-off workers) and (white) upper-middle class, in search for urban living outside central London boroughs. With the implementation of leisure spaces as well as eating and shopping facilities in the area (pubs, delis, a coffee shop and the farmer’s market), White challenges the idea of how belonging is articulated in Forest Gate and interconnects the continuation (and development) of social inequalities based on race and class, with the changing landscape and practices.

The following two chapters constitute the primary material (and the book’s most powerful chapters) of White’s argumentation about the effects that neoliberal policies, racism and violence have on young Black lives. Chapter 5 opens with experiential memories from two older residents of Newham and continues with three incidents of violence on Black youths that occurred in Newham in 2017 and 2018. Here, the author communicates incidents of hostility towards Black individuals with the aim of highlighting these acts of violence as a manifestation of reactionary government policies that have been in effect (with some variations) since early Immigration Laws (early 1960s), thus leading to the development of a hostile environment for Black British populations in Newham. By referring to incidents of police harassment and law enforcement regulations that were fundamentally racist (‘sus’ laws and ‘Stop and Search’ for instance), White remarks that ‘Black youth had been demonised as criminals or at the very least as having a propensity to crime’ (p. 85).

Chapter 6 is a highly personal account on violence that to an extent also reflects the context and thematic of the previous chapters. In February 2016, the author’s nephew Nico was lethally stabbed and after a few days in the hospital, his life support was turned off. Nico’s killers are all serving life sentences. It is a powerful and heart-breaking chapter to read, that imputes the pain of loss to a framework of official policies, regulations and control that perpetuate the very system of brutality over Black individuals that took Nico away. As White points out at the beginning of the chapter, ‘the societal conditions that make serious youth violence such a real possibility are embedded in at least four decades of enduring inequalities’ (p. 96).

The closing chapter is a recap of all the points and arguments White stressed throughout the book about how young Black lives matter ‘in a society where inequality, exclusion and violence are normative’ (p. 114). By addressing aspects of Newham’s changing landscape, discriminatory regulations on housing and employment and the representation of local Black community in public, White’s account constitutes a way to tackle selective forgetfulness on ‘the symbolic, structural and slow violence that occurs in young Black lives […]’ (p. 122). Regarding the methodological aspect of Terraformed, White has succeeded in creating an ethnographic enquiry of good quality with the framework of ‘hyper-local demarcation’ possessing a central role in capturing the lived experiences of Black youth in a ‘hostile’ and ever-shifting landscape. However, I would prefer to hear more from the older generation of Forest Gate as it would give the reader valuable insights towards a better understanding of their experiences in the inner-city regarding the conceptual themes of the book. Another interesting point that Terraformed does not bring up pertains to gendered identities in relation to the notions of class, race and violence.

Overall, Terraformed is a timely, critical account on injustices, racism and violence that Black youth lives undergo within the scope of neoliberalism, austerity and the changing landscape in Newham. The book stands equal next to other contributions in the particular field of social/race studies (Cresswell, 1996; Dawes, 2020; DiAngelo, 2019; Oluo, 2020; Tatum, 2017 [1997]) and it constitutes a useful source for students and practitioners of the field. Furthermore, what makes this book even more compelling is the author’s personal perspective and experiences that strengthen the credibility of her arguments while maintaining accessible language throughout the text. As the description on the back cover reads, Terraformed is an ‘insider ethnography’ of the area of research. This remark is substantiated by White’s strong family bonds with Forest Gate, a fact that renders her the ideal ethnographer and thus one of the book’s most captivating elements.

References

Cresswell T (1996) In Place/Out of Place: Geography, Ideology, and Transgression, new edn. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Google Scholar

Dawes AL (2020) Race Talk: Languages of Racism and Resistance in Neapolitan Street Markets. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Crossref Google Scholar

DiAngelo R (2019) White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. London and New York, NY: Penguin Books. Google Scholar

Oluo I (2020) So You Want to Talk About Race. New York, NY: Basic Books. Google Scholar

Tatum BD (2017 [1997]) Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? New York, NY: Basic Books. Google Scholar

Related articles

If you enjoyed this review, the following articles published in Urban Studies might also be of interest:

|

Spatialities of Ethnocultural Relations in Multicultural East London: Discourses of Interaction and Social Mix by Penny-Panagiota Koutrolikou Through the lens of two London boroughs, this paper explores the spatial dimensions of ‘living together’ and the ways that social mix, interaction and multicultural spaces affect intergroup relations. |

Playing the Ethnic Card: Politics and Segregation in London’s East End by Sarah Glynn This article takes a critical look at the exploitation of difference and at the impact of political forces of various kinds on ethnic segregation. |

Read more book reviews on the Urban Studies blog.

Comments

You need to be logged in to make a comment. Please Login or Register

There are no comments on this resource.