Mapping Gentrification and Displacement Pressure: An Exploration of Four Distinct Methodologies

by Benjamin Preis, Aarthi Janakiraman, Alex Bob, Justin Steil

- Created

- 21 Feb 2020, 10:03 a.m.

- Author

- Benjamin Preis, Aarthi Janakiraman, Alex Bob, Justin Steil

- DOI

- 10.1177/0042098020903011

Abstract: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0042098020903011#abstract

Mapping gentrification and displacement — where it’s happening, where it might happen — has been conducted by academics for over 20 years. In recent years, however, community groups, local media, and city governments have also taken to mapping gentrification, trying to understand its local extent and impacts.

We began this research curious as to whether these efforts were measuring the same thing. When a city says it is mapping gentrification, what are the underlying variables and weights? If you take four different methods and apply them all to the same city, will the same neighborhoods light up, or will the differing methods disagree?

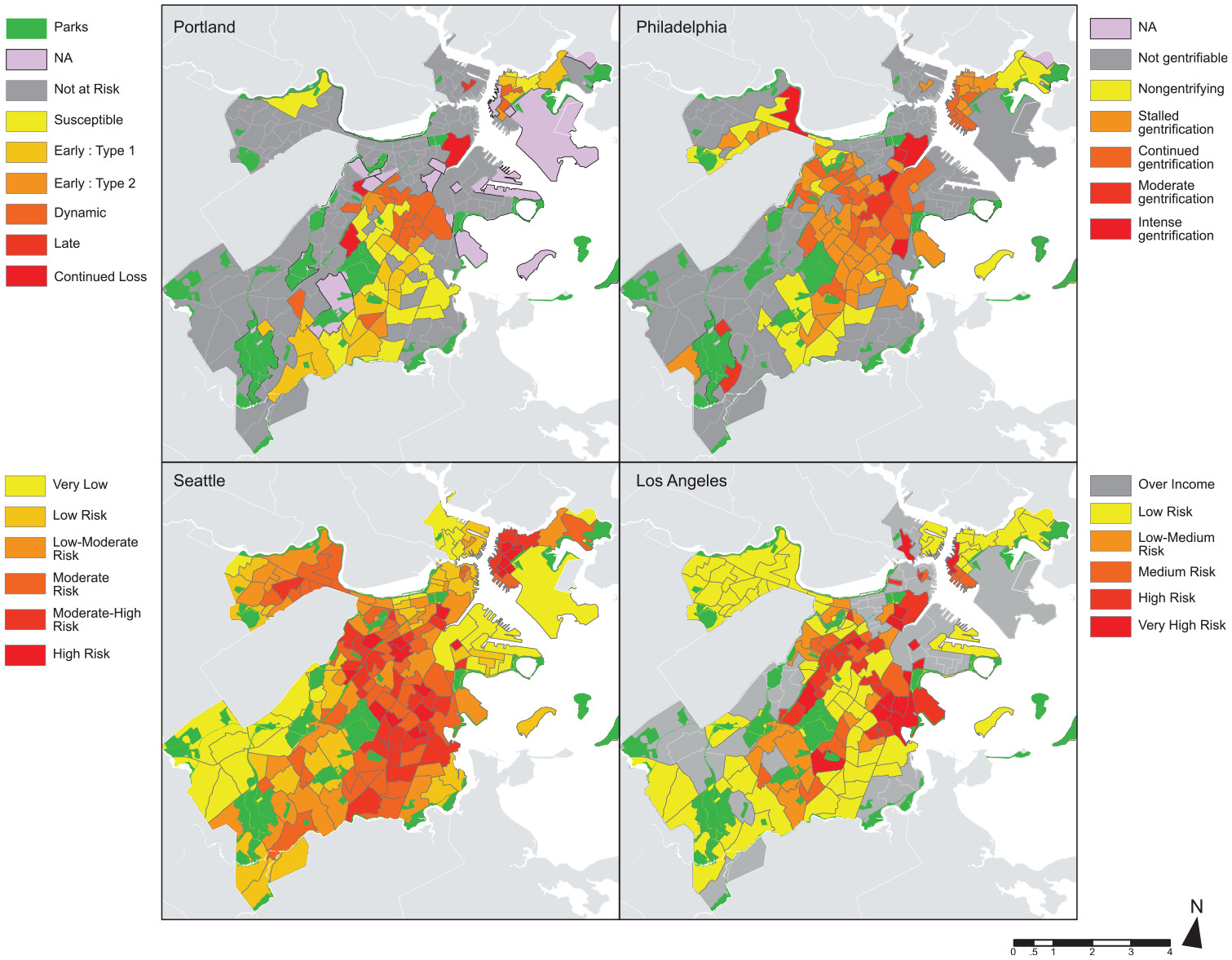

What is immediately obvious from the figure is how much the methods disagree in their results. In the Portland and Philadelphia methods, approximately half of Boston isn’t even considered gentrifiable. On the other extreme, the method from Seattle had no minimum cut off, and nearly two-thirds of the city is considered at some risk for gentrification-induced displacement. In fact, the four methods only agreed on seven census tracts out of Boston’s 180, seen below.

After identifying four cities that recently created gentrification and displacement maps — Philadelphia, PA; Los Angeles, CA; Portland, OR; and Seattle, WA — we took to replicating their methods in Boston, a city we knew well as it was just across the river from our campus at MIT. Consulting with the teams that made the original maps, we tried to replicate their models as closely as possible. Our main findings are in the image below.

Of these seven tracts, two of the tracts lie in northern Dorchester, two in northern Roxbury, one in Jamaica Plain, one in Downtown/Chinatown, and one in East Boston. These neighborhoods match with the anecdotal understanding of where gentrification is happening in Boston. While we do not suggest that identifying the intersection of all four methods will lead a practitioner to the “true” at-risk neighborhoods, it is telling of the demographic changes experienced in these neighborhoods that all four maps have included them.

As we dug deeper in order to understand our findings, we came to realize that the differing end results came about because they were based on differing theories of gentrification. The origin of the word “gentrification” came about from a sociological text in 1964, London, by Ruth Glass; gentrification was defined as the process of the landed gentry fixing up working class neighborhoods in the decades following World War II. As the concept has evolved both within and outside academia, different theories have developed as to what gentrification is, and how to measure it.

Some definitions of gentrification relate strictly to an influx of well-educated or high-income individuals. Other definitions of gentrification add racial and other social attributes. Still others build on these definitions and add government investment, private investment, and past disinvestment as possible risk factors. These definitions have informed the choice of variables included in each of the four mapping methods: among the 18 possible variables included overall, only two variables — income and education — were included in all four methods.

We hope that our findings will show practitioners and the public alike that, as one asks: “where is gentrification happening in my city,” they will recognize that gentrification is informed by local contextual history and factors. As such, mapping efforts should be adapted to the local conditions, and ground-truthed with local residents, to see how the outputs relate to local understandings of gentrification and its impacts.

Read the accompanying article on Urban Studies OnlineFirst: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0042098020903011

Comments

You need to be logged in to make a comment. Please Login or Register

There are no comments on this resource.